Oddcast episode

December 21, 2020

Allegra Baggio-Corradi on Niccolò Leonico Tomeo

Even casual enthusiasts of western esotericism have heard of the esoteric perennialist Platonism of the Florentine Renaissance, constructed by figures like Marsilio Ficino and Giovanni Pico della Mirandola. But what was going on in the rest of Italy at the time? With this interview we begin to answer that question, examining the fascinating life of Niccolò Leonico Tomeo (Νικόλαος Λεόνικος Θωμεύς) of Padua: humanist, priest, philosophic Christian theorist, and esotericist of a very different stamp to the Florentines.

Tomeo was the son of an emigré East Roman family who had moved to Italy during the final years of decline of the Empire; he thus grew up speaking Greek, giving him a marketable skill-set in fifteenth-century Italy. Born in Venice in 1456 (three years after the fall of Constantinople), he moved to Padua at a young age, and then traveled around Italy in pursuit of the complete set of liberal studies including medicine, classics, astrology, and so on. Living out the remainder of his life largely in Padua (then part of the Venetian Republic), he was a heavyweight in international humanist circles (corresponding with Erasmus of Rotterdam and Guillaume Budé, among others), the teacher of Pietro Bembo, the greatest poet of fifteenth-century Italy, and many other important luminaries. And he wrote at a time of exceptional intellectual freedom: the short window in which utterly heretical work like his could openly be published was soon to close, but, boy did he make the most of it while it lasted.

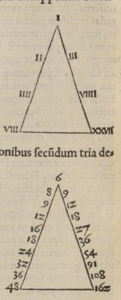

Tomeo was busy with largely the same materials as the Florentines – classical pagan texts, especially the newly-rediscovered (for them) riches of the Greek language, Christian theology, and the scientific inheritance of the medieval period – but integrated these materials into quite a different worldview. Padua was ‘a powerhouse of radical Aristoteleanism’ in contrast to Florence’s Neoplatonism, leading to radically different views on natural magic, the nature of matter, and a fascinating theory of the imaginative faculties.

But Tomeo also held many beliefs which we might consider radically Platonist: he was reading a lot of Proclus (and the Pseudo-Dionysius), and held both that an ineffable One is the supreme principle, and that we must be rigorous in our apophatic discourse about the One. Jesus and the Holy Spirit never make an appearance in his dialogues, and God Himself tends to be ‘the One’. He also had a theory of the efficacy of prayer in which prayer functions along Proclan lines. He believed in the pre-existence of souls (yes, he read Origen), and cyclical reincarnation every thousand years (yes, he read Plato). His thought on the therapeutic power of music is in some ways similar to that of Ficino (lutenists take note!).

Other delights to be found in this interview include a major work on divination, centred around the Oracle of Trophonius (see Episodes 69 and 70), a sympathetic and open reading of the traditional polytheist religion of the classical world (without any assumption that it might conflict with Christianity in a serious way), and an oracular pet pelican.

Works Cited in this Episode:

Primary:

- Erasmus of Rotterdam: Colloquia, 1529, treatise on ‘Knucklebones, or the Game of Tali’.

- Marsilio Ficino: the ‘Three Books on Life’ are the de vita libri tres or de triplici vita, written 1480-1489, published 1489.

- Pomponio Gaurico, Treatise on Sculpture, of which Tomeo is the main character, Firenze 1505.

Niccolò Leonico Tomeo: Tomeo lived from 1456 (Venice)-1531 (Padua). Select bibliography:

- 1508: first printed edition of Plutarch, edited by Toméo, Venice.

- 1516: translation of the Pseudo-Ptolemaic Inerrantium stellarum significationes, Venice.

- 1523: translation of Aristotle’s parva naturalia. Aristotelis Parva quae vocant Naturalia, Bernardino Vitali, Venice.

- 1524: Dialogues, including Trophonius, or On Divination, Venice.

- 1525: Opuscula, including a translation of the section of Proclus’ In Tim. on the generation of the soul.

- 1530: Second edition of Dialogues, with supplementary material, Paris.

- 1530: Opera omnia, Paris.

- 1531: Three Books on Various Histories, a multifarious work on natural history, Basel.

- 1540: posthumous translation of the last book on the movement of animals. Conversio in Latinum atque explanatio primi libri Aristotelis de partibus animalium… nunc primum ex authoris archetypo in lucem aeditus. G. Farri, Venice.

- 1542: Posthumous translation of Galen’s Letter to the Epileptic Child, Venice.

Secondary:

- Jacomien Prins. ‘The Music of the Pulse in Marsilio Ficino’s Timæus Commentary’. In Manfred Horstmanshoff, Helen King, and Claus Zittel, editors, Blood, Sweat and Tears. The Changing Concepts of Physiology from Antiquity into Early Modern Europe, pages 393–414. Brill, Leiden/Boston, 2012.

Themes

Aristoteleanism, Astral Magic, Interview, Natural Magic, Oracles, Origen, Proclus, Pseudo-Dionysius, Toméo, Venice

Comments

Comments are open to SHWEP members only

Join now to comment

Already a member? Log in here