Members-only podcast episode

An Antidote to Esotericism: Karen ní Mheallaigh on Lucian of Samosata

This is a special podcast episode for SHWEP members only

Already a member? Log in here to view this episode

[N.B. Apologies for the sound on this interview, which is really atrocious. The internet was not happy that day, and expressed its discontent with digital grumblings.]

Before diving headlong further into late antiquity, we thought that nothing could be more delightful than a quick, palate-cleansing return to the light-hearted, not-so-serious days of the Second Sophistic. And no writer of that period casts a more refreshing light on the whole field of esotericism than Lucian of Samosata (c. 125-c. 180 CE), antiquity’s master of the barbed satire and wry observer of the whole Græco-Roman scene. No one was safe when Lucian took up the stylus, but his particular targets were religion and philosophy (or at least the pretensions of philosophers). Plato and the Platonists are lambasted. Religious con-men come in for serious lampooning. The Olympian gods and their various cousins from other cultures (including the youngest member of the clan, Glycon the talking snake) are mocked mercilessly.

Lucian invented a new form: the comical prose dialogue, drawing on Plato’s invention, the philosophical dialogue, among other genres. He uses it, as well as more traditional prose narrative forms, to blur the lines between truth and falsehood, reality and text, gods and men, honest men and criminals. He was, we think, at least reasonably popular in his own day (though perhaps not in the élite circles to which he aspired), but it was in the early modern period that his star truly ascended: authors from Rabelais to Voltaire and Swift absolutely loved Lucian, and stole as much from him as they could. He is, in many ways, the perfect antidote to esotericism, or at least to taking esotericism too seriously. In the course of his exposeés of religious huxterism, fraud, and credulity, however, he is also one of our best sources on the Græco-Roman popular ‘occult’, on ghost-lore, magical practices and the people who practised them, beliefs about cosmic ascent, and much more. In other words, perhaps against his will, Lucian is a must-read author for students of ancient esotericism.

Interview Bio:

Karen ní Mheallaigh is Professor of Classics at Johns Hopkins University. Her Academia page shows the breadth of her scholarship, much of which is focused on Lucian, the Second Sophistic more generally, and the world of Græco-Roman fiction-writing. She has a beloved dachshund called Sweep, which is suspiciously close to Shwep.

Recommended Reading:

Introduction to Lucian and his context

- Bartley, A. (ed.) 2009. A Lucian for our Times. Newcastle upon Tyne.

- Billault, A. (ed.) 1994. Lucien de Samosate. Actes du colloque international de Lyon organisé au Centre d’Études Romaines et Gallo-Romaines les 30 septembre – 1er octobre 1993, Lyon. Paris.

- Branham, R.B. 1989. Unruly Eloquence. Lucian and the Comedy of Traditions. Cambridge, Mass..

- Goldhill, S. 2002. ‘Becoming Greek, with Lucian,’ in Who needs Greek? Contests in the Cultural History of Hellenism. Cambridge, 60-107.

- Jones, C.P. 1986. Culture and Society in Lucian. Cambridge, MA.

- Hall, J. 1981. Lucian’s Satire. New York, NY.

- Whitmarsh, T. 2001. Greek Literature and the Roman Empire. Oxford.

Tex/ translation/ commentaries on Lucian’s Verae Historiae (True Stories) and Philopseudes (Lover of Lies)

- Costa, C.D.N. (trans.) 2009. Lucian: Selected Dialogues. Oxford World’s Classics.

- Ebner, M., Gzella, H., Nesselrath, H.-G. and Ribbat, E. (edd.), Lukian: Die Lügenfreunde oder: Der Unglaubige. Stuttgart.

- Georgiadou, A. and Larmour, D.H.J. 1998. Lucian’s Science Fiction Novel True Histories: Interpretation and Commentary. Leiden.

- von Möllendorff, P. 2000., Auf der Suche nach der verlogenen Wahrheit. Lukians Wahre Geschichten. Tübingen.

- Ogden, D. 2007. In search of the Sorcerer’s Apprentice: the Traditional Tales of Lucian’s Lover of Lies. Swansea.

Lucian: truth, lies, fiction, philosophy …

- Laird, A. 2001. ‘Ringing the Changes on Gyges: Philosophy and the Formation of Fiction in Plato’s Republic,’ JHS 121, 12-29.

- Laird, A. 2003. ‘Fiction as a Discourse of Philosophy in Lucian’s Verae Historiae,’ in S. Panayotakis, M. Zimmerman & W. Keulen (edd.), The Ancient Novel and Beyond. Leiden and Boston, 115-127.

- ní Mheallaigh, K. 2014. Reading fiction with Lucian: Fakes, Freaks and Hyperreality. Cambridge.

- ní Mheallaigh, K. 2018. ‘Lucian’s Alexander: Technoprophecy, Thaumatology and the Poetics of Wonder,’ in M. Gerolemou (ed.), Recognizing miracles in antiquity and beyond. Berlin/ Boston, 225-56.

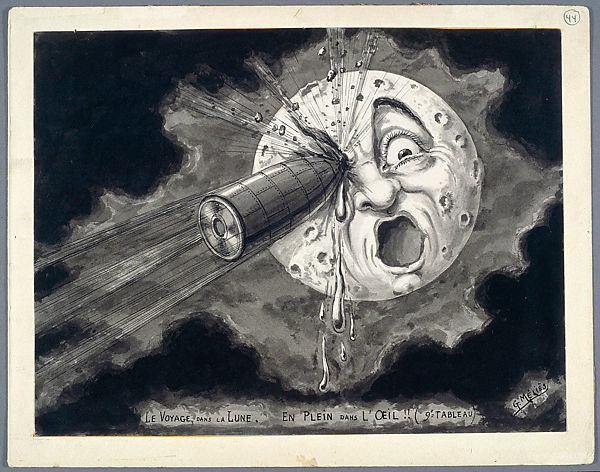

- ní Mheallaigh, K. 2019: ‘Reflections on Lucian’s Lunar Mirror: Speculum Lunae and an Ancient Telescopic Fantasy,’ in L. Diamontopoulou and M. Gerolemou (edd.), Mirrors and Mirroring: from Antiquity to the Early Modern Period. Bloomsbury Academic, 165-75.

- ní Mheallaigh, K. 2020. The Moon in the Greek and Roman Imagination: Selenography in Myth, Literature, Science and Philosophy. Cambridge.

- Rütten, U. 1997. Phantasie und Lachkultur: Lukians “Wahre Geschichten.” Tübingen.

Lucian’s Nachleben

- Baumbach, M. 2002. Lukian in Deutschland: eine Forschuhngs- und Rezeptionsgeschichtliche Analyse vom Humanismus bis zur Gegenwart. Munich.

- Hilton, J.L. 2005. ‘Lucian and the Great Moon Hoax of 1835,’ Akroterion 50, 87-108.

- Lauvergnat-Gagnière, C. 1988. Lucien de Samosate et le lucianisme en France au XVIe siècle: athéisme et polémique. Geneva.

- Ligota, C. and Panizza, L. (edd.) 2007. Lucian of Samosata vivus et redivivus. London and Turin.

- Robinson, C. 1979. Lucian and his Influence in Europe. London.

- Romm, J.S. 1989. ‘Lucian and Plutarch as Sources for Kepler’s Somnium,’ Classical and Modern Literature 9, 97-107.

Comments

Comments are open to SHWEP members only

Join now to comment

Already a member? Log in here