Podcast episode

January 5, 2018

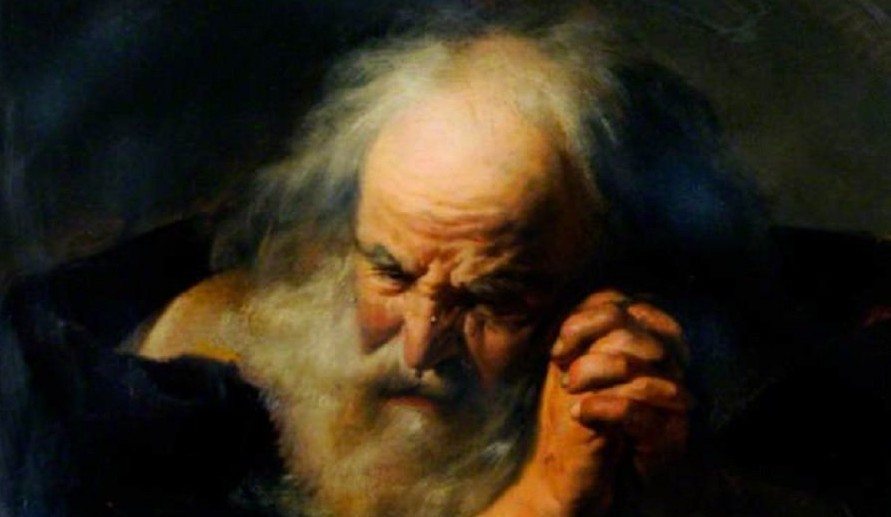

Episode 19: Riddle Me This: Heraclitus of Ephesus

Heraclitus of Ephesus made one well-known contribution to the history of western thought: his dictum that ‘nature loves to hide’ has been cited down the ages by philosophers, alchemists, mystics, and scientists, as the locus classicus of the inherent trickiness of nature, her ability to present one appearance to the everyday seeker and a radically different one to the thinker who penetrates more deeply into her depths. But Heraclitus also made important ‘secret’ contributions to the long history of western esoteric thought. We discuss the most important of these, his difficult-to-interpret idea of logos, which seems to have been the starting-point for a long evolution of this term from a complex word meaning ‘account, report, reckoning, speech, rational thought, solution’ to an even more complex term implying all of these meanings but also serving as a metaphysical principle, an occult property of things whereby they were informed by a divine plan or rational telos.

Along the way we don’t neglect some of the fascinating details of Heraclitus, not least of which are his propensity to speak in riddles, his general obscurity, and his overall esoteric approach to the open expression of the truth.

Works Discussed in this Episode:

- Aristotle, Metaphysics A 986a 22-b2

- Hadot, P., 2006. The Veil of Isis: An Essay on the History of the Idea of Nature. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

- Kahn, C., 1979. The Art and Thought of Heraclitus. Cambridge University Press, London/New York, NY/Melbourne.

Recommended Reading and Listening:

The History of Philosophy Podcast’s episode on Heraclitus is a wonderful intro to the guy. See also the Stanford article on Heraclitus. The wikipedia article on riddles is really cool.

- Mortley, R., 1986. From Word to Silence. Hanstein, Bonn contains fascinating material on the rise of the idea of a metaphysical logos in Greek thought.

Themes

Heraclitus, Logos, Philosophy, Pre-Socratic Philosophy, Riddles

Bernie Lewin

September 15, 2019

In your survey of the meanings of ‘logos’ there is no mention of the one found in Pythagorean mathematics, which is ‘ratio’. This seems neglectful considering what happened between the 5th century and the stoic-Christianity logos. Eudoxus’s partial solution to the problem of the irrationals was to shift from the arithmetic ratio (1:2) to ratio in general (and so include 1:sqrt2 and 1:Pi). This is famously preserved in Euclid Defn 5, Bk 5. Eudoxus seems to have been working closely and esoterically with Plato when he came to this solution and Plato seems to have shifted the focus of research in accord with it. Subsequent esoteric Platonism and stoicism celebrated the logos as the principle of differentiation, as the original-one-becoming-two (this 1st born often called ‘Dyad’).

This is interesting for future development but it might also be important to a discussion of Heraclitus. Firstly, if we consider that Euclid preserves in a formalised manner the mathematical teaching of the Pythagorean up to his time (300 BCE), then the many theories concerning logos and ana-logia might suggest this as an important part of Pythagorean teachings already before Plato. Secondly, it might suggest a more general meaning outside Pythagoreanism. It might suggest that it concerned difference and differentiation, and in that way how things are related and bound to each other. This could also have a parallel in reasoning, as in ratio-nalisations of nature. Finally, Heraclitus has these series of opposites with a common ‘ratio’ for example (eg the ratio of ‘death’).

Christopher Eads

September 1, 2022

Given the tendency of many classical and late antique Greek sages to ascribe their wisdom to that of the ancient Egyptians, it is somewhat surprising that there is no mention here of just such a possible precursor to Heraclitis’s proto-view of speech configuring reality. Eminent German Egyptologist Jan Assmann writes in The Search for God in Ancient Egypt:

As a verbal power that emanated from speech, akhu was a means that deities, especially deities of knowledge, such as Isis, Thoth, and Re, had at their disposal. With the radiant power of their sacred words, Isis and Thoth could exorcise the enemy and stop the sun in its course, and Isis could heal her suffering child Horus and revive the dead Osiris. In the cult, speech also made use of this power of language, in that it was expressed as the language of deities. – p. 88

Assmann goes on to devote an entire chapter to drawing out this idea with regard to the historical record, at another point even prefiguring a sort of early theurgy:

Only deities could make use of the “radiant power of words,” along with the king, insofar as the latter acted as a god, and the priests to whom the king delegated his priestly function, when they appeared in divine roles and were authorized to use sacred words. – p. 92

I admit that I am new to the SHWEP, and perhaps this is discussed in a later podcast, but as this is such a “leitmotif” within any discussion of Western Esotericism, I felt it deserved a mention here.

Earl Fontainelle

September 7, 2022

Dear Christopher,

Thanks for the comments. Agreed that many Greek sages attributed their wisdom to Egypt, and agreed that there are some intriguing parallels here with the Egyptian theological ideas and some stuff we find in Heraclitus. If I were a specialist like the I might well be able to say more in this context, but sadly my understanding of ancient Egyptian thought is VERY limited (undoubtedly a problem for this podcast, as we are trying to be pretty thorough).

However, there is a major question about what Heraclitus means by logos, an ambiguity that he himself almost certainly intended to vex anyone who read his works, and it is at any rate safe to say that it either doesn’t mean ‘speech’, or that, if it does, it also means other things (like ‘ratio’, see the previous comment, or perhaps something like ‘quasi-mathematical structure’).

You are right, though, that the idea of a linguistic basis to reality, or of a divine language (a linked idea) does appear a lot in the podcast going forward! Our Oddcast interview with Juan Acevedo might be a meaty place to start.

Maziar Hashemi-Nezhad

April 6, 2023

The Vedic Ṛta, the Mazdian Asha and the Heraclitan Logos, all three highly nuanced yet share a large overlap of meaning; Rule, Truth and Cosmic Order. Thus, another way to plumb the depths of the Heraclitan Logos is to trace out the Logos though its eastern ‘alleles’ via comparative analysis of the three.

The idea that Heraclitus’s Logos has its antecedent in the East is not far-fetched since Heraclitus lived in Achaemenid Ionia and would have had contact with the Persian Magi and their beliefs. Moreover, the significance and centrality of Fire to both Heraclitus and the Magi adds further evidence to this thesis.

The Logos may be best understood as Heraclitus’s synthesis of Eastern and Greek thoughts.

Earl Fontainelle

April 6, 2023

It’s an intriguing idea. We don’t have enough evidence to talk about influence here, but I agree that the comparative project is attractive!

We might want to go further (just for fun) and bring Zeno of Citium, the founder of Stoicism, into the discussion: he is either a Phoenician or a Greek-speaker from a Phoenician milieu (but our main source, Diogenes Laërtius, just asserts that he’s a Phoenician), and so has a priori some potential connection with near-eastern theological ideas (although I recognise how vague and pathetic that is, even as I write it). Zeno follows Heraclitus in privileging fire as the divine element, and this divine fire is the universal logos. We haven’t the slightest evidence, as far as I’m aware, for anything particularly ‘Persian’ in Phoenician thought in Zeno’s time, and yet I cannot help but wonder if there is something Mazdaic in the philosophical choices Zeno makes, which might have influenced the particular uses he makes of Heraclitus.

Was there a ‘fiery’ vibe in near-eastern religious and philosophical ideas at the time? If we had more certain knowledge of Achaemenid-era Mazdaist religious thought, we might be able to say ‘yes’ with greater certainty. But I’d say we can only speculate so far based on the practice of fire-altars and so forth.