Members-only podcast episode

‘This Fortunate City’: Constantinople Considered as Talisman, Part I

This is a special podcast episode for SHWEP members only

Already a member? Log in here to view this episode

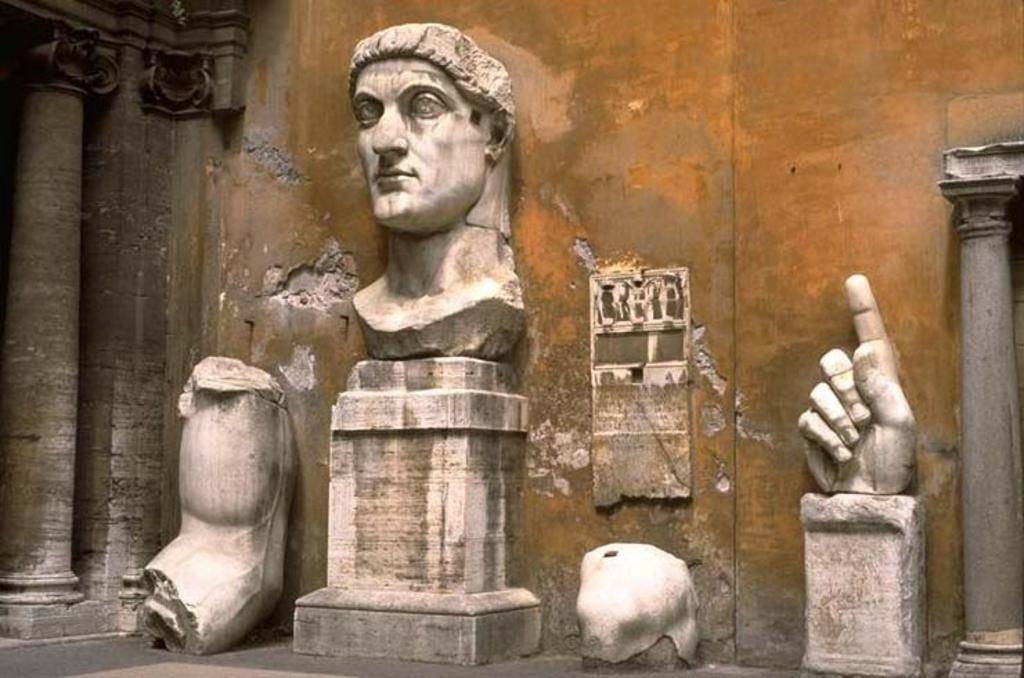

Following on from the discussion of esoteric architecture in our Hagia Sophia episode, we survey some of the evidence for the lore about talismanic Constantinople as she was held to be by her own denizens. Constantine’s city was full of statues, both grand and humble; it was quickly understood, by Constantinopolitans, that these were in fact various talismans protecting the city from things like mosquitoes and rambunctious horses.It was also quickly understaood that thee wonders were set up by none other than the great authority on talismans, Apollonios of Tyana (who had been dead for centuries).

She was also founded as a purpose-built capital for the eastern empire; surely one would not undertake such a momentous foundation without consulting the best diviners available? We survey the evidence for belief in the katarchic horoscope of Constantinople, and its association with the great authority, Vettius Valens (who had also been dead for centuries).

Works Cited in this Episode:

Primary:

The Parastaseis: fifteen chapters discuss statues in relation to prophecies, portents, or astronomy/astrology: 27, 5a, 5d, 8, 16, 20, 21, 28, 40, 41, 54, 61, 64, 65, 69 (reference from Benjamin Anderson. Classified Knowledge: The Epistemology of Statuary in the Parastaseis Syntomoi Chronikai. Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies, 35:1–19, 2011., p. 6). The reference to Constantine’s visions having occurred at Constantinople is also from this article, p. 13.

Manuel Komnenos to Michæl Glykas on astrology: see Imperatoris Manuel Comneni et Michael Glycæ disputatio in Franz Cumont et al., editors. Catalogus Codicum Astrologorum Graecorum, volume 12 vols. in 20 parts. Lamertin, Brussels, 1898–1953, V.1, 108–25 for Manuel’s letter, 125–40 for Glykas’ reply.

Secondary:

Albrecht Berger. Das apokalyptische Konstantinopel. Topographisches in apokalyptischen Schriften der mittelbyzantinischen Zeit. In Wolfram Brandes and Felicitas Schmieder, editors, Endzeiten. Eschatologie in den monotheistischen Weltreligionen, number 16 in Millennium-Studien, pages 135–55. De Gruyter, Berlin/New York, NY, 2008. We quote p. 148. The original German: ‘Apollonios von Tyana spielt in der Konstantinopler Lokalsage schon seit den sechsten Jahrhundert eine gewisse Rolle als angeblicher Urheber von Zauberstatuen, durch die allerlei Unheil von der Stadt ferngehalten werden konnte, und als solcher tritt er auch noch in den Patria auf. Apollonios lebte tatsächlich im ersten Jahrhundert nach Christus, wird aber von einigen Quellen kurzerhand in die Zeit Konstantins des Großen versetzt, um sein Wirken in Konstantinopel plausibler zu machen.’

Averil Cameron and Judith Herrin, editors. Constantinople in the Early Eighth Century: The Parastaseis Syntomoi Chronikai. Introduction, Translation and Commentary. Brill, Leiden, 1984; we quote pp. 36-7.

Gilbert Dagron. Constantinople imaginaire. Études sur le recueil des Patria. Presses Universitaires de France, Paris, 1984; we quote pp. 107. On Apollonios’ many talismans, see pp. 107–14.

Dorian Greenbaum. The Origins of Questions in Astrology. In Luís Campos Ribeiro and Charles Burnett, editors, Astrologers at Work: Essays on the Practices and Techniques of Astrology in Memory of Helena Avelar, pages 1–58. Brill, Leiden/Boston, MA, 2026.

Stephan Heilen. Ancient Scholars on the Horoscope of Rome. Culture and Cosmos, 11:43–86, 2007.

Paul Magdalino. Occult Science and Imperial Power in Byzantine History and Historiography (9th-12th Centuries). In Paul Magdalino and Maria Mavroudi, editors, The Occult Sciences in Byzantium, pages 119–62. La Pomme d’Or, Geneva, 2006.

Recommended Reading:

SHWEP Talismanic Constantinople Recommended Reading

Travis Wade ZINN

January 12, 2026

This episode opens a line of inquiry I would be very interested to see pursued further. If Constantinople can be approached as a talismanic city, it raises the broader question of Christian capitals as architectures of metaphysical management, not merely symbolic or devotional environments.

What seems especially compelling is the possibility that such cities were designed as multipurpose spaces: capable of stabilizing power and containing inherited religious forces, while also preserving initiatic grammars legible only to a minority of readers. In this light, architecture and statuary do not simply instruct or commemorate; they regulate access—binding certain meanings while leaving others latent.

This perspective naturally invites comparison with Rome and the Vatican, where the continuity of form, reuse of pre-Christian material, and choreographed spatial sequences suggest a long memory of metaphysical technique rather than accidental survival. I would be very interested in your thoughts on whether the category of the “talismanic city” can be extended in this direction—and, if so, which sources you would recommend for studying esoteric architecture and initiation at the urban scale.

Earl Fontainelle

January 12, 2026

I think the Vatican is a great example here, though not purpose-built, and we’ll need to explore it further down the line. But as for sources, I don’t know of any, and the SHWEP might be the best one, or at least will be once we get a few more cities under our belt. But someone correct me if there is a talismanic cities literature out there! I want to read it, too.

Travis Wade ZINN

January 12, 2026

hanks, Earl — that’s helpful, and I agree. The Vatican does seem to be a special case: not purpose-built in the way Constantinople was, but nevertheless accumulating into a highly orchestrated environment through centuries of reuse, layering, and symbolic continuity.

My sense is that the issue isn’t so much the absence of sources as the absence of a category. The relevant material is scattered across work on sacred architecture, memory systems, imaginal theory, and late antique and Renaissance magic, but rarely treated at the scale of the city as an operative metaphysical whole. Dagron is an obvious anchor, but figures like Rykwert, Yates, Belting, and Couliano all gesture toward this terrain without quite naming it.

In that light, SHWEP may end up doing something genuinely original here: allowing the idea of the talismanic city to emerge inductively, city by city, rather than forcing it into a premature theoretical frame. If so, I suspect the Vatican will eventually prove unavoidable.

Also, looking positively to the future, talismanic cities might not only be instruments of control, but also potential incubation environments: structured spaces in which new forms of spiritual and cultural life can gestate. The recovery of architectural intelligence may prove central to any durable renewal and transformation.

Earl Fontainelle

January 13, 2026

I dig it. And not only instruments of control and potential incubation environments, but also instruments of liberation, as we shall see anon in the podcast!

James Butler

January 13, 2026

A fascinating episode – and fun to hear you shift to the demotic pronunciation as the centuries proceed.

It’s maybe an unanswerable question, or perhaps something you’ll speculate on later in the series, but do you have a sense that this urban-talismanic imaginary flows into the later literature? I am thinking, of course, of the famous city of Adocentyn in the Picatrix/Ghayat; my understanding is that there is a staggering number of exempla of such mythic-talismanic cities in the Arabic literature, but it’s not a language I have. I quote the Latin from the Pingree edition (1986, p.188 ff.):

‘Sunt etiam magi qui in hac sciencia et opere se intromiserunt Caldei; hinamque in hac perfectiores habentur sciencia. Ipsi vero asserunt quod Hermes primitus quandam domum ymaginum construxit, ex quibus quantitatem Nili contra Montem Lune agnoscebat; hic autem domum fecit Solis. Et taliter ab hominibus se abscondebat quod nemo secum existens valebat eum videre. Iste vero fuit qui orientalem Egipti edificavit civitatem cuius longitudo duodecim miliariorum consistebat, in qua quidem construxit castrum quod in quatuor eius partibus quatuor habebat portas. In porta vero orientis formam aquile posuit, in porta vero occidentis formam tauri, in meridionali vero formam leonis, et in septentrionali canis formam construxit. In eas quidem spirituales spiritus fecit intrare qui voces proiciendo loquebantur; nec aliquis ipsius portas valebat intrare nisi eorum mandato. Ibique quasdam arbores plantavit, in quarum medio magna consistebat arbor que generacionem plantavit, in quarum medio magna consistebat arbor que generacionem fructuum omnium apportabat. In summitate vero ipsius castri quandam turrim edificari fecit, que triginta cubitorum longitudinem attingebat, in cuius summitate pomum ordinavit rotundum, cuius color qualibet die usque ad septem dies mutabatur. In fine vero septem dierum priorem quem habuerat recipiebat colorem. Illa autem civitas quotidie ipsius mali cooperiebatur colore, et sic civitas predicta qualibet die refulgebat colore. In turris quidem circuitu abundans erat aqua, in qua quidem plurima genera piscium permanebant. In circuitu vero civitatis ymagines diversas et quarumlibet manerierum ordinavit, quarum virtute virtuosi efficiebantur habitantes ibidem et a turpitudine malisque languoribus nitidi. Predicta vero civitas Adocentyn vocabatur.’

Yrs etc – a Metic in the City of Hermes

Earl Fontainelle

January 14, 2026

James,

I think there is a complex relationship between the ‘real’ talismanic cities and the fictional ones, and that it goes both ways. In founding Constantinople, the emperor and whoever was helping him will have surely had both Plato’s ideal cities and the New Jerusalem somewhere in the backs of their minds, right? (To say nothing of the many other possible fictional templates they could have been thinking about …) This goes even if we completely discount the theurgic possibilities discussed in Part II of the episode (stay tuned). And we can see this play out in the apocalyptic tradition and in later myths about Constantinople, where she gets involved with the New Jerusalem in all sorts of ways; the two sometimes blend into each other. Was Justinian thinking along these lines when he declared the Hagia Sophia the new Temple, and himself the new Solomon? Easy to imagine.

At any rate, yes, I think that a lot of later magical cities found in various forms of utopian literature might well be profitably considered alongside bricks-and-mortar talismanic cities, to see what resonances there are in both directions, if you see what I mean.